Sati or Suttee is a banned funeral custom, where a widow either voluntarily or by compulsion self-immolates (Anumarana or Anugamana) on her husband’s pyre, or commits suicide in some other manner, following her husband’s death. It is regarded to have emerged from the warrior aristocracy in the northern Indian subcontinent and later found ground in many areas in Southeast Asia. Unrelenting campaigns of reformers like Ram Mohan Roy and William Carey led to ban of Sati in India starting from the passage of Bengal Sati Regulation in 1829. Later, the Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987, was enacted that prohibits any kind of aid, encouragement, and glorifying the practice of sati.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice))

How and why did the practice of Sati come into existence?

Origin of Sati is still a subject of debate. The custom founds mention in the 3rd century BC, however evidence of the practice followed by widows of kings appeared starting from the 5th to 9th centuries CE. It is considered that Sati originated from the warrior aristocracy in the northern Indian subcontinent and was particularly observed by aristocratic families of some Hindu communities. With time it gained popularity starting the 10th century CE. The practice eventually extended to other groups from the 12th through 18th century CE. It was also witnessed in many other parts in Southeast Asia outside of the Indian subcontinent in places like Indonesia and Vietnam. Sati however was never extensively observed across India and also does not have scriptural sanction.

Some reliable extant records on Sati date back prior to rule of the Gupta Empire (c. 400 CE). It was recorded by Greek historian Aristobulus of Cassandreia that while he accompanied Alexander the Great on his expedition to India in c. 327 BCE, he came to know that widows of certain tribes took pride in immolating themselves with their husbands and those who refused were disgraced. Diodorus Siculus (c. 1st century BCE) mentioned that Cathaei people, who lived between the Beas and Ravi rivers observed widow-burning. He said that younger wife of Indian captain Keteus, who died in Battle of Gabiene (316 BCE), immolated herself in her husband’s funeral pyre. Diodorus mentioned that Indians married out of love and when such marriages hit the rocks, many a times the wives poisoned the husbands and then moved on with new lover. Thus a law was passed to stop such murders. It stated that either the widow embrace death joining her husband or spends rest of her life in widowhood. Axel Michaels mentioned that first inscriptional evidence of Sati dating back in 464 CE is from Nepal and that in India is from 510 CE. Initial records of Sati indicate that it was infrequently observed by general public.

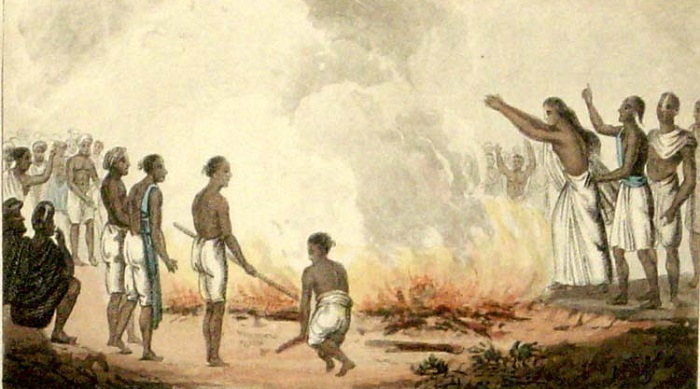

Image Credit :https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)

Image Credit :https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)

Henry Yule and Arthur Coke Burnell suggested in their Hobson-Jobson (1886) that Suttee (sati) was an early practice of tribes of Thracians in southeast Europe, Russians near Volga and some tribes of Tonga and Fiji islands. They also compiled list on Sati that date from 1200 CE to the 1870s CE. It included the case of Keteus. Archaeologist Elena Efimovna Kuzmina observed that practice of co-cremation of a man and a woman/wife was symbolic rather than a strict custom in both the burial practices of the ancient Asiatic steppe Andronovo cultures (fl. 1800–1400 BCE) and the Vedic Age. It is considered by many that the custom increased in the centuries that were marked with Muslim invasions and their expansion in the Indian subcontinent.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice), https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-sati-195389, https://theculturetrip.com/asia/india/articles/the-dark-history-behind-sati-a-banned-funeral-custom-in-india/)

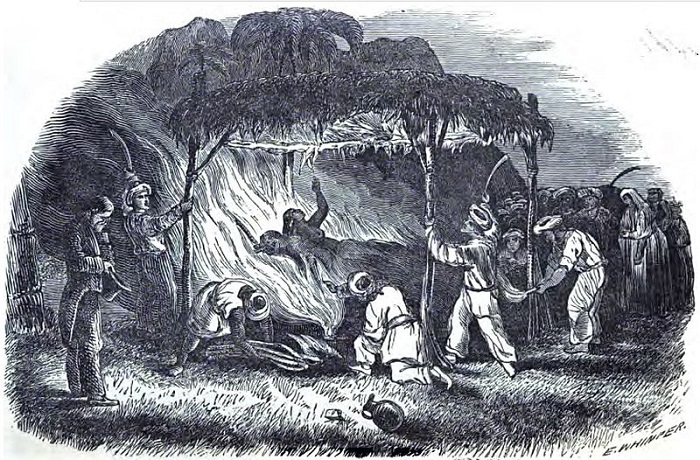

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)

How widespread was the practice of sati?

There is no consensus on when, where, why and how the practice of Sati spread. Anant Sadashiv Altekar opined that Sati became really widespread in India during c. 700–1100 CE, especially in Kashmir. A few statistics on its development was given by him. Prior to 1000 CE, there were either two or three attested cases of Sati in Rajputana where the custom later gained prominence. At least 20 instances of Sati were found from 1200 to 1600 CE. There are 11 inscriptions associated with Sati from 1000 to 1400 CE and 41 from 1400 to 1600 CE in the Carnatic region. According to Altekar there was a gradual rise in the spread of Sati which probably reached its peak in the first decades of 19th century when the British started to intervene.

One model, as mentioned by Anand A. Yang, suggests that Sati became really widespread during the Islamic invasions of India as a practice to safeguard honour of women whose men were killed. Sashi said the argument is that the custom became effective to safeguard honour from the Muslims invaders who had reputation of committing mass rape of women of captured cities. However cases of Sati prior to such Muslim invasions are also palpable. For instance a 510 CE inscription, regarded as a sati stone, in Eran elucidates that wife of Goparaja, a vassal of Bhanugupta, immolated herself on her husband’s pyre. A particular form of Sati called Jauhar, mass self-immolation by women, was observed by Rajputs during era of Hindi-Muslim conflicts to avoid capture, enslavement and rape.

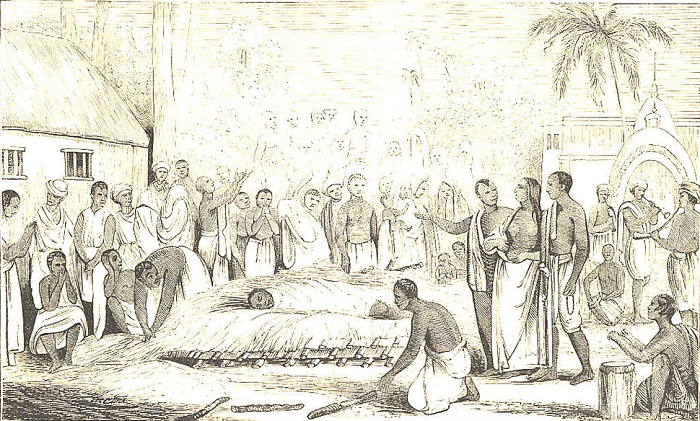

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)

Another theory suggest Sati had spread from Kshatriya to others castes as a cultural phenomenon and part of “Sanskritization” and not due to wars. However this theory was disputed as it did not elucidate why the upper caste Brahmins would follow customs of Kshatriyas. Hawley’s theory suggested that the practice commenced as a “nonreligious, ruling-class, patriarchal” ideology and eventually expanded emerging as a status symbol of purity, courage and honour during Rajput wars and following the Muslim invasions in India. Such theories however do not explain why the practice persisted till the colonial era, especially prominently in the once largest subdivision (presidency) of British India, the Bengal Presidency. Three theories suggest reason for continuation of Sati by such time. Firstly it was believed that Sati was supported by Hindu scriptures by the 19th century. Secondly it was used by corrupt neighbours and relatives as a means to eliminate the widow who inherited property of her deceased husband. According to the third theory, the widow observed Sati to avoid extreme poverty situation of the 19th century.

Indian Ocean trade routes paved way for emergence of Hinduism in Southeast Asia and with this Sati also spread in the new locations between the 13th and 15th century. According to Odoric of Pordenone, widow-burning was observed in Champa kingdom (in present south/central Vietnam) in early 1300s. Altekar mentioned that with settlement of Hindu migrants in Southeast Asian islands, Sati extended to places like Java, Sumatra and Bali. The Dutch colonial records mention that in Indonesia, Sati was as rare custom, observed in royal households. During the 15th and 16th centuries, lords and the wives of deceased kings of Cambodia burnt themselves voluntarily. European traveller accounts suggest practice of widow-burning in 15th century Mergui in Myanmar (Burma). According to some sources, the custom was practiced in Sri Lanka, however only by the queens and not by ordinary women.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice), https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-sati-195389)

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)

Who Abolished the Custom of Sati in India?

Annemarie Schimmel mentioned that Mughal Emperor Akbar was against Sati but showed great regard for the widows who wanted to join their deceased husbands on the pyre. An order was issued by Akbar in 1582 to restrict any forceful use of Sati. However whether Akbar issued a ban on the custom is not yet clear. Akbar’s son Jahangir succeeded him in the early 17th century by which time Sati was observed by Muslims of Rajaur (Kashmir) who were converted to Islam by Sultan Firoz. Reza Pirbhai mentioned that as per memoirs of Jahangir, the practice was observed by both Hindus and Muslims in his regime and the Kashmiri Muslim widows observed it by immolating or burying themselves alive with their deceased husbands. Such practices as also other customary practices were prohibited by Jahangir in Kashmir. Sheikh Muhammad Ikram mentioned that sixth Mughal emperor Aurangzeb issued an order in 1663 directing that officials should never allow woman-burning in the Mughal Empire.

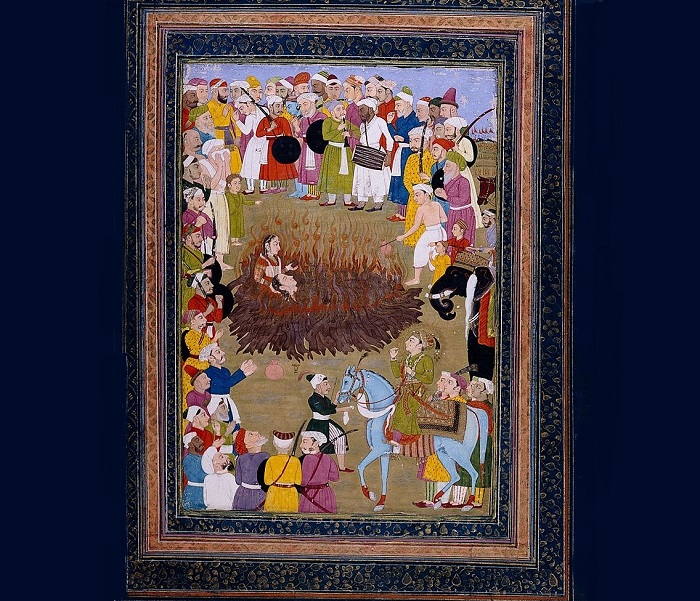

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice)

Following the Portuguese conquest of Goa in 1510, the Portuguese banned Sati there, however it was still observed in the area. The practice was banned by the Dutch in their colonies in Chinsurah and the French in theirs in Pondicherry. During the 18th century, individual British officers also attempted to limit or ban the custom, however nothing fruitful happened. Starting from early 19th century, the evangelical church in Britain, and its members in India, began campaigns against the practice. The campaign leaders included William Wilberforce and William Carey. Carey along with William Ward and Joshua Marshman known as the Serampore Trio published essays that vehemently condemned Sati. A founder of the Brahmo Samaj, Raja Ram Mohan Roy who experienced forceful Sati of his sister-in-law, remained one of the prominent leaders who championed the cause of banning Sati. He started his crusade in 1812 and went to a great extent including persuading widows against observing Sati visiting cremation grounds; forming watch groups for such pursuit; writing and distributing articles showing that Sati was not required as per Hindu scripture; and seeking support from Bengali elite class in prohibiting such social evil. In Gujarat, the founder of the Swaminarayan sect, Sahajanand Swami, spoke against Sati. The efforts of both Christian and Hindu reformers bore fruit when the then Governor-General of India Lord William Bentinck effected ban on Sati by issuing Bengal Sati Regulation in India under East India Company rule, in 1829. The regulation made Sati illegal in all Indian jurisdictions and subject to prosecution in criminal courts. The law was extended to Madras and Bombay on February 2, 1830 and by 1861 all the princely states legally banned Sati. Finally a proclamation from Queen Victoria in 1861 led to the issue of a general ban on Sati.

After the September 1987 Sati of Roop Kanwar produced a public outcry, the Government of Rajasthan enacted Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 which became an Act of the Parliament of India with passage of The Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 in 1988. According to the law supporting, encouraging, forcing, glorifying or attempting to commit sati is illegal and punishable.

(Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sati_(practice))

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ram_Mohan_Roy

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ram_Mohan_Roy

Lesser-known facts on Sati Pratha

- Sati is derived from name of goddess of marital felicity and longevity in Hinduism, Sati, who self-immolated after she and her husband Lord Shiva were humiliated by her father Daksha.

- During its peak, Sati claimed thousands of widow-burning every year.

- Some widows poisoned themselves before committing Sati.

- The practice of sati, however, spared pregnant widows.

- Some suggest that Sati might have inspired Catholic witch burnings.

- Official reports mention that around 30 cases of Sati were documented in India between 1943 and 1987.

- According to some sources, the custom still exists in some parts of India and is held in high regards.

(Source: https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/sati-pratha-facts-275586-2015-12-04, https://www.ranker.com/list/sati-hindu-custom-widows-women-burning-themselves-alive/richard-rowe)