Fast Facts

Official Name: Indian Statutory Commission

Year of Constitution: November 1927

Number of Members: Seven

Year of Arrival: 1928

Headed by: Sir John Allsebrook Simon

Assisted by: Clement Richard Attlee

Outcome: Government of India Act, 1935

The Simon Commission refers to a group of seven MPs from the United Kingdom, constituted to suggest constitutional reforms for British India. The Commission consisted of only British members, headed by one of the senior British politicians, Sir John Allsebrook Simon. Clement Richard Attlee, who was chosen as Simon’s assistant, arrived in India in the year 1928, along with the rest of the Commission members. The purpose of their visit was to study the constitutional reform in British India and to suggest more such reforms. Since the British administration had failed to include even a single Indian in the Commission, it was strongly opposed by national leaders and freedom activists.

Image Credit http://www.shareyouressays.com/essays/essay-on-simon-commission-constitution-opposition-reaction-challenges/89848

Background – Why Was Simon Commission Sent to India?

To expand the participation of Indians in government affairs, the Parliament of the United Kingdom had passed an act called ‘The Government of India Act 1919.’ The act introduced the system of diarchy in British India, which was opposed by Indian nationalist leaders, who demanded the administration to review the system. The act envisaged a system of review of reforms after ten years to study and analyse the constitutional progress and to bring in more reforms. Though the review was due in the year 1929, the Conservative government, which was in power back then, decided to form the Commission that would study the constitutional progress of India in the late 1920s. The reason behind forming the Commission earlier was the Conservative government’s fear of losing to the ‘Labour Party’ in the upcoming elections. Since the Conservative government did not want the ‘Labour Party’ to take over British India, it constituted a commission consisting of seven British MPs to study the constitutional progress in British India as promised earlier.

Members of the Commission

Sir John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon

He had held senior Cabinet posts for almost three decades and went on to become one of the three politicians to have served as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Foreign Secretary, and as the Home Secretary of Britain.

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee

Having served as Simon’s assistant in the Commission, Clement Attlee played a crucial role as UK’s Prime Minister during India’s independence.

Harry Levy-Lawson, 1st Viscount Burnham

Harry Levy-Lawson joined the ‘Liberal Unionist Party’ and then sat in the ‘House of Commons’ from late 1880s to early 1900s.

Sir Edward Cecil George Cadogan

In 1922, Cadogan entered the ‘House of Commons’ as a Member of Parliament, before representing the Commission in 1927.

Vernon Hartshorn

A prominent British politician from the ‘Labour Party,’ Hartshorn served as a Member of Parliament from the year 1918 until his demise in 1931.

George Richard Lane-Fox, 1st Baron Bingley

Lieutenant-Colonel George was a Conservative politician, who served as the Secretary for Mines for a total of six years.

Donald Sterling Palmer Howard

He became the Member of Parliament for Cumberland North after being elected at the 1922 general elections. In 1927, he became the seventh and last member to represent the ‘Indian Statutory Commission.’

Image Credit : https://www.1hindi.com/simon-commission-details-in-hindi

Protests – Why Was Simon Commission Boycotted?

People in India were infuriated and felt insulted, for the Commission, which had been constituted to analyse and recommend constitutional reforms for India, did not have a single Indian member. The Simon Commission was strongly opposed by the Congress and other nationalist leaders and common people.

Many protests were carried out individually as well as in groups, urging the British administration to review the constitution of the Commission. In December 1927, the Indian National Congress in its meeting in Madras resolved to boycott the Commission. It also challenged the Secretary of State for India, Lord Birkenhead, to draft a constitution that would please the Indians. Led by Mohammed Ali Jinnah, some of the members of the ‘Muslim League’ too, had made up their minds to boycott the Commission.

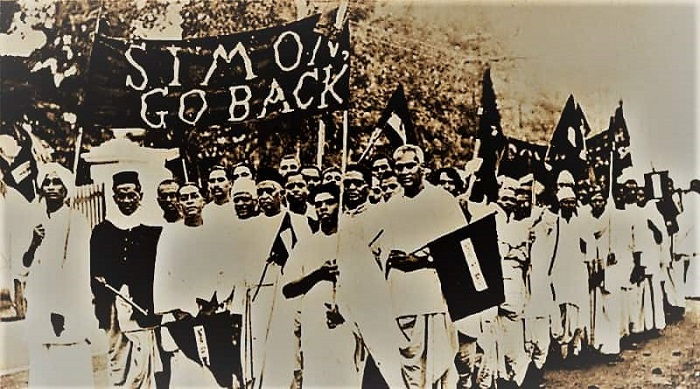

The Commission, headed by Sir John Allsebrook Simon, left England in January 1928 and reached India on February 3, 1928. As soon as the Commission’s arrived in Bombay, it was greeted by thousands of protestors, who demanded the Commission to go back. Many were seen holding placards and other sign boards that had the words ‘Go Back Simon’ written on them. There were nation-wide strikes and people greeted the Commission with black flags. Wherever the commission went, it received the same response.

The Death of Lala Lajpat Rai

On October 30, 1928, the Commission decided to visit Lahore. Just like other places, the people of Lahore decided to protest against the Commission. Led by one of the most prominent Indian nationalist leaders Lala Lajpat Rai, a group of people was protesting against the Commission’s Lahore visit. The protest was peaceful and violence was reported, but in an act of retaliation, James A. Scott, the then superintendent of police, ordered a ‘lathi charge’ (baton charge) against the protestors. Many claimed that Scott had personally assaulted Lala Lajpat Rai, injuring him severely in the process. In spite of being subjected to brutal blows at the hands of James A. Scott and his team of policemen, Lala Lajpat Rai addressed the crowd even before the arrival of medical help and stated that the ‘blows struck at him were the final set of nails in British India’s coffin.’

Lala Lajpat Rai never completely recovered from the injuries. On November 17, 1928, the fiery nationalist leader died of cardiac arrest. Though the doctors believed that his death could have been catalyzed by the injuries caused by the baton charge, the British government denied its role in Lajpat Rai’s death. Lala Lajpat Rai’s untimely demise saddened the entire country and Bhagat Singh, who did not share Lala lajpat Rai’s methods of attaining independence, but respected the elderly leader for his efforts in the freedom movement, vowed to take revenge on James A. Scott. This led to the murder of the then assistant superintendent of police, John P. Saunders, who was killed by Bhagat Singh and Rajguru in a classic case of mistaken identity.

Image Credit http://mypaintingsmylife.weebly.com/shaheed-bhagat-singh.html

Aftermath

In its May 1930 report, the Commission proposed the eradication of diarchy system and suggested the establishment of representative government in various provinces. Much before the Simon Commission’s report, Motilal Nehru submitted his ‘Nehru Report’ in September 1928 to counter the Commission’s charges, which suggested that Indians still lacked constitutional consensus. The ‘Nehru Report’ pushed for dominion status for India with complete internal self-government.

The British government had seen the opposition the Simon Commission faced in India. While the report was still to be published, the British government tried to calm down people by saying that the opinion of Indians will be taken into account in any such future exercise and that the natural outcome of constitutional reforms will be dominion status for India.

Image Credit : https://www.meghnet.in/2015/08/simon-commission.html

The Government of India Act 1935 was a result of the recommendations of the Simon Commission. The Government of India Act 1935 forms the basis of many parts of the Indian constitution. According to the act, responsible government was to be formed at the provincial level. In the first provincial elections held in 1937, Congress governments came to power in almost all the provinces, which encouraged the Indians to intensify their fight for complete freedom.

One of the members of the Commission, Clement Richard Attlee had endorsed the final report of the Simon Commission, but by 1933 he felt that the British rule was not able to make the necessary social and economic reforms required for India’s progress.