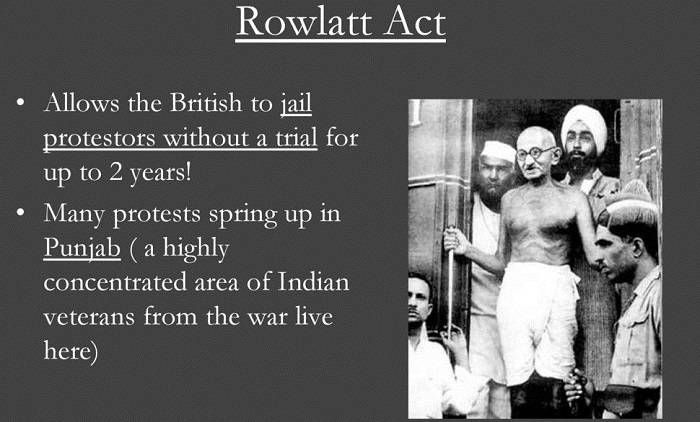

Also Known As: The Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919, Black Act

Passed by the Imperial Legislative Council in February 1919, the Rowlatt Act enabled British government to jail anyone suspected of plotting to overthrow them for as long as two years without trial and also to try them summarily without any jury. Based on the report of the committee headed by Justice S.A.T. Rowlatt, it replaced the Defence of India Act (1915) instituted during the First World War with a permanent law that gave the British more power over Indians. The repressive legislation was strongly opposed by the Indian leaders, especially Mahatma Gandhi, who organised a movement against it that led to the infamous Jallianwala Bagh massacre in April 1919 and subsequently, the Non-Cooperation Movement.

Major Provisions of Rowlatt Act

Popularly referred to as the ‘Rowlatt Act’, the ‘Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act of 1919’ was legislated by the British to discourage Indians from rising against them by supressing revolutionary groups and depriving the Indians of their right to personal expression and liberty. The main provisions of the ‘Rowlatt Act’ envisaged the arrest and deportation of any person on mere suspicion of sedition and revolt; the trial of those arrested by special tribunals established for that purpose; and the declaration of possession of treasonable literature as a punishable offence.

Image Credit : http://slideplayer.com/slide/12118846/

The repressive Act also provided for the press to be controlled even more strictly; gave sweeping powers to the police to search premises and arrest anyone merely on suspicion without needing a warrant; the right to indefinitely detain suspects without trying them and to conduct in-camera trials for forbidden political acts without any jury. The draconian legislation recommended by Justice Rowlatt also denied the undertrials the right to information regarding the identity of their accusers as well as the nature of the evidence presented against them for their alleged crimes. After completion of their sentences, the convicts had to deposit securities to ensure their good behaviour and were also prohibited from participating in political, religious, or educational activities.

The two controversial bills were introduced in the Imperial Legislative Council in February 1919 and despite very strong opposition by the Indians, became law in March 1919. Prominent among those opposing the Act were independence activists like Mazhar Ul Haq, Madan Mohan Malviya, and Mohammed Ali Jinnah, all of whom joined the rest of their Indian colleagues in resigning from the Council after unanimously voting against the Act.

Image Credit : https://www.hindustantimes.com/punjab/revisiting-jallianwala-100-years-on-bloodbath-on-baisakhi-the-massacre-that-shook-the-british-raj/story-wjIbGE4PjWi59qwQMpY5MJ.html

Reaction of Indians to Rowlatt Act

The ‘Rowlatt Act’ was vehemently opposed by all the Indian leaders who felt that it was extremely repressive and the Indian public too was extremely angry and resentful. Mahatma Gandhi, especially, was a very strong critic of the proposed legislation as he felt that it was morally incorrect to punish a group of people for a crime committed by only one or a few. Realising the futility of constitutional opposition to the Act, Gandhi organised for the first time, a ‘hartal’ that envisaged the masses suspending all business and instead gathering in public spaces to fast and pray to peacefully demonstrate their opposition to the law with civil disobedience. The ‘Rowlatt Satyagraha’, as the movement came to be known, however, left the British completely unmoved, as they did not perceive the peaceful ‘hartal’ to be a threat.

Repercussions of Rowlatt Act

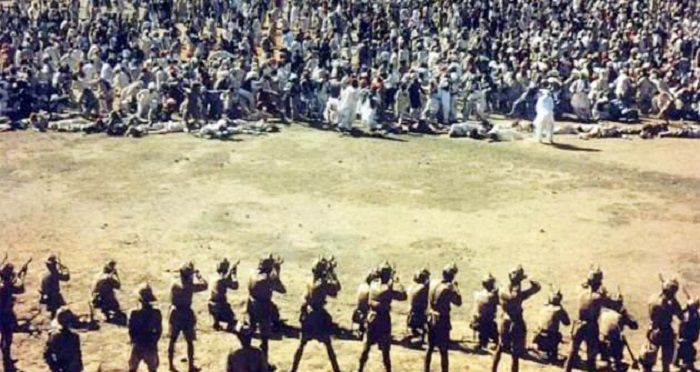

As the Rowlatt Act became law in March 1919, the protests became more vocal and aggressive, especially in Punjab, where rail, telegraph and communication systems were disrupted. Before the end of the first week of April, the protests had peaked and Lahore, especially, was on the boil. Two of the most visible faces of the protests and champions of the ‘Satyagraha’ movement; Dr. Satya Pal and Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew were taken into custody by the police and secretly transported away. Protesters against the arrests who gathered at the residence of the Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar to demand their release were fired upon by the police; several people were killed and the enraged mob attacked and torched a number of banks and other government buildings, including the railway station and the Town Hall. The escalating violence took the lives of at least five Europeans and anywhere between 8 and 20 Indians. The violence spread to other parts of Punjab and more government buildings were set on fire, communications disrupted, and railway lines damaged.

Image Credit : https://www.dailyvedas.com/the-most-atrocious-laws-imposed-by-the-british-in-india/

The leaders of the ‘hartal’ in Amritsar met on 12 April 1919 to pass resolutions against the Rowlatt Act and to protest the arrests of Satya Pal and Kitchlew. They also decided that a public protest meeting would be held the following day at Jallianwala Bagh. In the morning of 13 April 1919, the day of the traditional festival of ‘Baisakhi’, the acting military commander, Colonel Reginald Dyer, anticipating further agitation and violence announced several restrictions on the movement and assembly of people. However, the common people did not heed it or understood the implications and continued to gather at Jallianwala Bagh. While there were some protesters, a lot many of them were simply those on their way back after offering their prayers at the Golden Temple and still others celebrating the harvest festival ‘Baisakhi’ after the local horse and cattle fair closed early. Even though Colonel Dyer had come to know of the gathering, he did nothing to disperse the crowd of Sikhs, Muslims, and Hindus, which by mid-afternoon had swelled to about 25,000.

At 5.30 in the evening, an hour after the planned protest meeting had started, Colonel Dyer arrived with his troops at Jallianwala Bagh, sealed off the sole exit, and ordered indiscriminate firing on the peaceful and unarmed crowd without any warning. The ten minute shooting spree and the ensuing stampede caused the deaths of around 1,000 persons though the official figure put out by the British was a mere 379. The British administration did their best to suppress news of the massacre from getting out, however, very soon, the whole of India came to know of the butchery and widespread outrage ensued. However, it was only in December 1919 that the details of the event reached Britain. While some hailed Colonel Reginald Dyer as a hero, others condemned his dastardly act, and the Hunter Commission instituted subsequently found an unrepentant Dyer guilty of grave error though it did not take any action against him. Later, he was disciplined, passed over for promotion, and relieved of all duties in India.

Image Credit : https://steemit.com/india/@pranab-sarkar/a-short-introduction-the-rowlatt-act-3

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre left Mahatama Gandhi horrified and he lost all faith in the British to be reasonable. Always a firm believer in the strength of non-violent opposition, Gandhi started the Non-Cooperation Movement promising his countrymen ‘Swaraj’ in one year. The movement envisaged Indians boycotting offices and factories, withdrawing from British-run schools, civil services, the police and the military besides forsaking goods and clothing made by the British. Although opposed by many veteran Indian political leaders, Gandhi’s idea received strong support from the younger generation of Indian nationalists. The success of the Non-Cooperation movement shocked the British, however, dismayed by the violence at Chauri Chaura where a police station was burnt by a mob killing some 22 policemen inside, Mahatama Gandhi called off the Non-Cooperation movement fearing that it could become even more violent in the days to come.