A Brief History of the British East India Company

Between early 1600s and the mid-19th century, the British East India Company lead the establishment and expansion of international trade to Asia and subsequently leading to economic and political domination of the entire Indian subcontinent. It all started when the East India Company, or the “Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading with the East Indies”, as it was originally named, obtained a Royal Charter from Queen Elizabeth I, granting it “monopoly at the trade with the East”. A joint stock company, shares owned primarily by British merchants and aristocrats, the East India Company had no direct link to the British government.

Through the mid-1700s and early 1800s, the company came to account for half of the world’s trade. They traded mainly in commodities exotic to Europe and Britain like cotton, indigo, salt, silk, saltpetre, opium and tea. Although initial interest of the company was aimed simply at reaping profits, their single minded focus on establishing a trading monopoly throughout Asia pacific, made them the heralding agents of British Colonial Imperialism. For the first 150 years the East India Company’s presence was largely confined to the coastal areas. It soon began to transform from a trading company to a ruling endeavor following their victory in the Battle of Plassey against the ruler of Bengal, Siraj-ud-daullah in the year 1757. Warren Hastings, the first governor-general, laid down the administrative foundations for the subsequent British consolidation. The revenues from Bengal were used for economic and military enrichment of the Company. Under directives from Governor Generals, Wellesly and Hastings, expansion of British territory by invasion or alliances was initiated, with the Company eventually acquiring major parts of present day India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar. In 1857, the Indians raised their voice against the Company and its oppressive rule by breaking out into an armed rebellion, which historians termed as the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857. Although the company took brutal action to regain control, it lost much of its credibility and economic image back home in England. The Company lost its powers following the Government of India Act of 1858. The Company armed forces, territories and possessions were taken over by the Crown. The East India Company was formally dissolved by the Act of Parliament in 1874 which marked the commencement of the British Raj in India.

Founding of the Company

The British East India Company was formed to claim their share in the East Indian spice trade. The British were motivated the by the immense wealth of the ships that made the trip there, and back from the East. The East India Company was granted the Royal Charter on 31 December, 1600 by Queen Elizabeth I. The charter conceded the Company monopoly of all English trade in lands washed by the Indian Ocean (from the southern African peninsula, to Indonesian islands in South East Asia). British corporations unauthorized by the company treading the sea in these areas were termed interlopers and upon identification, they were liable to forfeiture of ships and cargo. The company was owned entirely by the stockholders and managed by a governor with a board of 24 directors.

Coat of Arms for the English East India Company

Image Credit : alfa-img.com http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/23/Coat_of_arms_of_the_East_India_Company.svg/2000px-Coat_of_arms_of_the_East_India_Company.svg.png

Early Voyages

The first voyage of the company left in February 1601, under the commandership of Sir James Lanchaster, and headed for Indonesia to bring back pepper and fine spices. The four ships had a horrendous journey reaching Bantam, in Java in 1602, left behind a small group of merchants and assistants and returned back to England in 1603.

The second voyage was commandeered by Sir Henry Middleton. The third voyage was undertaken between 1607 and 1610, with General William Keeling aboard the Red Dragon, Captain William Hawkins aboard the Hector and the Captain David Middleton directing the Consent.

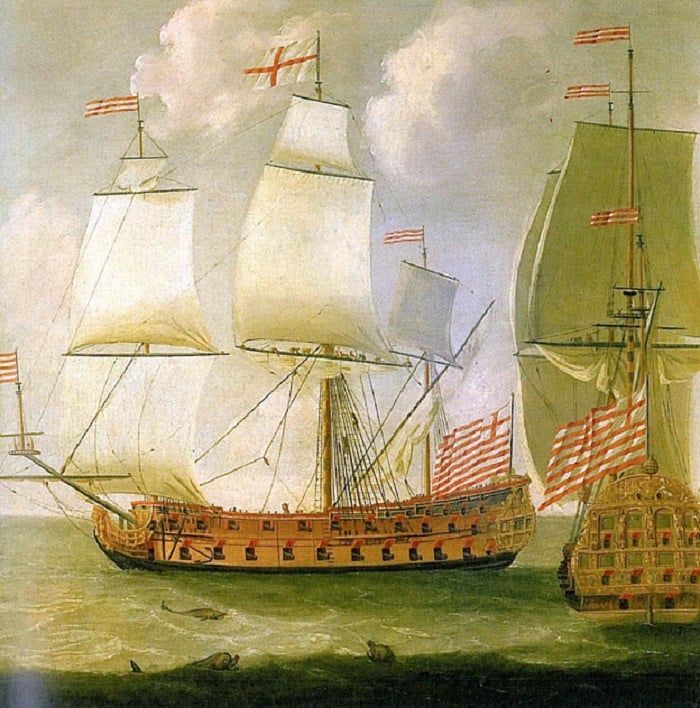

East India Company Ships, 1685

Image Credit : britishempire.co.uk http://www.britishempire.co.uk/images4/eastindiacompanyshipslarge.jpg

Establishment of Foothold in India

The Company’s ships first arrived in India, at the port of Surat, in 1608. In 1615, Sir Thomas Roe reached the court of the Mughal Emperor, Nuruddin Salim Jahangir (1605–1627) as the emissary of King James I, to arrange for a commercial treaty and gained for the British the right to establish a factory at Surat. A treaty was signed with the British promising the Mughal emperor “all sorts of rarities and rich goods fit for my palace” in return of his generous patronage.

Expansion

Trading interest soon collided with establishments from other European countries like Spain, Portugal, France and Netherlands. The British East India Company soon found itself engaged in constant conflicts over trading monopoly in India, China and South East Asia with its European counterparts.

After the Amboina Massacre in 1623, the British found themselves practically ousted from Indonesia (then known as The Dutch East Indies). Losing horribly to the Dutch, the Company abandoned all hopes of trading out of Indonesia, and concentrated instead on India, a territory they previously considered as a consolation prize.

Under the secure blanket of Imperial patronage, the British gradually out-competed the Portuguese trading endeavor, Estado da India, and over the years oversaw a massive expansion of trading operations in India. The British Company’s win over the Portuguese in a maritime battle off the coast of India (1612) won them the much desired trading concessions from the Mughal Empire. In 1611 its first factories were established in India in Surat followed by acquisition of Madras (Chennai) in 1639, Bombay in 1668, and Calcutta in 1690. The Portuguese bases at Goa, Bombay and Chittagong were ceded to the British authorities as the dowry of Catherine of Braganza (1638–1705), Queen consort of Charles II of England. Numerous trading posts were established along the east and west coasts of India, and most conspicuous of English establishment developed around Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras, the three most important trading ports. Each of these three provinces was roughly equidistant from each other along the Indian peninsular coastline, and allowed the East India Company to commandeer a monopoly of trade routes more effectively over the Indian Ocean. The company started steady trade in cotton, silk, indigo, saltpeter, and an array of spices from South India. In 1711, the company established its permanent trading post in Canton province of China, and started trading of tea in exchange for silver. By the end of 1715, in a bid to expand trading activities, the Company had established solid trade footings in ports around the Persian Gulf, Southeast and East Asia.

The Mughal emperor Shah Alam hands a scroll to Robert Clive, the governor of Bengal

Image Credit : mapstoryblog.thenittygritty.org http://mapstoryblog.thenittygritty.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2000.jpg

Towards Complete Monopoly

In 1694, the House of Commons voted “that all the subjects of England had an equal right to trade to the East Indies unless prohibited by act of Parliament.” Under pressure from wealthy influential tradesmen not associated with the Company. Following this the English Company Trading to the East Indies was founded with a state-backed indemnity of £2 million. To maintain financial control over the new company, existing stockholders of the old company paid a hefty sum of £315,000. The new company could hardly make a dent in the established old company markets. The new company was ultimately absorbed by the old East India Company in 1708. A tripartite venture was established between the state, the old and the new trading companies under the banner of United Company of Merchants of England Trading to the East Indies. The following few decades saw a bitter tug of war between the company lobby and the British Parliament to acquire permanent establishment rights which the latter was hesitant to relinquish in view of the immense profits the company brought. The united company lent to the government an additional £1,200,000 without interest in exchange of renewal of charter until1726. In 1730, the charter was renewed until 1766, in exchange of the East India Company lowering the interests on the remaining debt amount by one percent, and contributed another £200,000 to the Royal treasury. In 1743, they loaned the government another £1,000,000 at 3% interest, and the government prolonged the charter until 1783. Effectively, the company bought monopoly of trading in the East Indies by bribing the Government. At every juncture when this monopoly was expiring, it could only affect a renewal of its Charter by offering fresh loans and by fresh presents to the Government.

The French were late to enter the Indian trading markets and consequently entered into fresh rivalry with the British. By the 1740s rivalry between the British and the French was becoming acute. The Seven Years war between 1756 and 1763 effectively stumped out the French threat led by Governor General Robert Clive. This set up the basis of Colonial monopoly of East India Company in India. By the 1750s, the Mughal Empire was in a state of decadence. The Mughals, threatened by the British fortifying Calcutta, attacked them. Although the Mughals were able to acquire a victory in that face-off in 1756, their victory was short-lived. The British recaptured Calcutta later that same year. The East India Company forces went onto defeat the local royal representatives at the battle of Plassey in 1757 and at Buxar in 1764. Following the Battle of Buxar in 1764, the Mughal emperor signed a treaty with the Company allowing them to oversee the administration of the province of Bengal, in exchange for a revised revenue amount every year. Thus began the metamorphosis of a mere trading concern to a colonial authority. The East India Company became responsible for administering the civil, judicial and revenue systems in one of India’s richest provinces. The arrangements made in Bengal provided the company direct administrative control over a region, and subsequently led to 200 years of Colonial supremacy and control.

Regulation of the Company’s Affairs

Throughout the next century, the East India Company continued to annex territory after territory until most of the Indian subcontinent was effectively under their control. From the 1760s onward, the government of Britain pulled the reins of the Company more and more, in an attempt to root out corruption and abuse of power.

As a direct repercussion of the military actions of Robert Clive, the Regulating Act of 1773 was enacted which prohibited people in the civil or military establishments from receiving any gift, reward, or financial assistance from Indians. This Act directed the promotion of the Governor of Bengal, to the rank of Governor General over the entire Company-controlled India. It also provided that nomination of Governor General, though made by a court of directors, would be subject to the approval of the Crown in conjunction with a council of four leaders (appointed by the Crown), in future. A Supreme Court was established in India. The justices were appointed by the Crown to be sent out to India.

William Pitt’s India Act (1784) established government authority over political policy making which needed to be approved through a Parliamentary regulatory board. It imposed the Board of Control, a body of six commissioners, above the Company Directors in London, consisting of the Chancellor of the Exchequer and a Secretary of State for India, together with the four councilors appointed by the Crown.

In 1813 the Company’s monopoly of the Indian trade was abolished, and, under the 1833 Charter Act, it lost its China trade monopoly as well. In 1854, the British Government in England ruled for the appointment of a Lieutenant-Governor to oversee regions of Bengal, Bihar and Odisha and the Governor General was directed to govern the entire Indian Colony. The Company continued its administrative functions until the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857.

Takeover of the Company by the British Crown

The brutal and rapid annexation of native Indian states by introduction of unscrupulous policies like the Doctrine of lapse or on the grounds of inability to pay taxes along with forcible renunciation of titles sparked widespread discontent among the country’s nobility. Moreover, tactless efforts at social and religious reforms contributed to spread of discomfiture among the common people. The sorry state of Indian soldiers and their mistreatment compared to their British counterparts in the armed forces of the Company provided the final push towards the first real rebellion against the Company’s governance in 1857.Known as the Sepoy Mutiny, what began as soldiers protest soon took epic proportions when disgruntled royalties joined forces. The British forces were able to curb the rebels with some effort, but the munity resulted in major loss of face for the Company and advertised its inability to successfully govern the colony of India. In 1858, the Crown enacted the Government of India Act, and assumed all governmental responsibilities held by the company. They also incorporated the Company owned military force into the British Army. The East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act was brought in effect on January 1, 1874 and the East India Company was dissolved in its entirety.

Half Anna coins during the East India Company rule in India

Image Credit : indiacoin.wordpress.com https://indiacoin.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/1845.jpg

Legacy of the East India Company

Although the East India Company’s colonial rule was hugely detrimental to the interest of the common people due to the exploitative nature of governance and tax implementation, there is no denying the fact that it brought forward some interesting positive outcomes as well.

One of the most impactful of them was a complete overhaul of the Justice System and establishment of the Supreme Court. Next big important impact was the introduction of postal system and telegraphy which the Company arguably established for its own benefit in 1837. The East Indian Railway Company was awarded the contracts to construct a 120-mile railway from Howrah-Calcutta to Raniganj in 1849. The transport system in India saw improvements in leaps and bounds with the completion of a 21-mile rail-line from Bombay to Thane, the first-leg of the Bombay-Kalyan line, in 1853.

Artist’s impression of the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857

Image Credit : factsninfo.com http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-pfaSUdfpdus/VYzg12YpB0I/AAAAAAAAA1E/D2yozS213S8/s640/The_Relief_of_Lucknow.jpg

The British also brought forth social reforms by abolishing immoral indigenous practices through acts like the Bengal Sati Regulation in 1829 prohibiting immolation of widows, the Hindu Widows’ Remarriage Act, 1856, enabling adolescent Hindu widows to remarry and not live a life of unfair austerity. Establishment of several colleges in the principal presidencies of Calcutta, Bombay and Madras was undertaken by the Company governance. These institutions contributed towards enriching young minds bringing to them a taste of world literature, philosophy and science. The educational reforms also included encouragement of native citizens to sit for the civil services exams and absorbing them into the service consequently.

The Company is popularly associated with unfair exploitation of its colonies and widespread corruption. The humongous amounts of taxes levied on agriculture and business led to man-made famines such as the Great Bengal famine of 1770 and subsequent famines during the 18th and 19th centuries. Forceful cultivation of opium and unfair treatment of indigo farmers lead to much discontent resulting in widespread militant protests.

The positive aspects of social, education and communication advancements were overshadowed largely by the plundering attitude of the Company rule stripping its dominions bare for profit.